Bulletin of Sri Aurobindo International

Centre of Education

Bulletin du Centre International d'Éducation Sri Aurobindo

Août 1985

SRI AUROBINDO ASHRAM

Pondicherry (India)

Edited & Published by

Harikant C. Patel

Sri Aurobindo Ashram

Pondicherry - 605 002

Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers

for India No. R. N. 8890/57

All Rights Reserved

No matter appearing in this journal or part

thereof may be reproduced in any form,

except small extracts for purposes of re-

view, without the written permission of

the Publishers.

ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION RATES EFFECTIVE FROM 1986

|

Inland |

Foreign |

|

Rupees English-French Edition: 20 English-French-Hindi Edition: 25 |

U.S. $ English-French Edition: 7.00 English-French-Hindi Edition: 8.00 |

Airmail Subscription Rates:

| Europe & Asia: U.S. $ 14.00 | America & Canada: U.S. $ 18.00 |

(To be paid in U.S. $ or its equivalent)

Printed by

Amiyo Ranjan Ganguli

At Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press

Pondicherry- 605 002

Printed in India

The Kena Upanishad

|

In this Bulletin issue we continue to reprint The Kena Upanishad, Sri Aurobindo's last translation of and commentary on the Kena. First serialised in the monthly Arya review during 1915 and 1916, it was later brought out as a book in 1962.

Chapter 13 of Sri Aurobindo's commentary is presented here.

|

Dans ce numéro du Bulletin, nous poursuivons la réimpression de la Kéna Oupanishad, selon la dernière traduction qu'en a faite Sri Aurobindo et avec ses commentaires. Cet ouvrage a tout d'abord paru mensuellement dans la revue Arya au cours des années 1915 et 1916, puis a été publié sous forme de livre en 1952.

Nous donnons ici le chapitre 13 des commentaires de Sri Aurobindo. |

|

13. The Parable of the Gods

From its assertion of the relative knowableness of the unknowable Brahman and the justification of the soul's aspiration towards that which is beyond its present capacity and status the Upanishad turns to the question of the means by which that high-reaching aspiration can put itself into relation with the object of its search. How is the veil to be penetrated and the subject consciousness of man to enter into the master-consciousness of the Lord? What bridge is there over this gulf? Knowledge has already been pointed out as the supreme means open to us, a knowledge which begins by a sort of reflection of the true existence in the awakened mental understanding. But Mind is one of the gods; the Light behind it is indeed the greatest of the gods, Indra. Then, an awakening of all the gods through their greatest to the essence of that which they are, the one Godhead which they represent. By the mentality opening itself to the Mind of our mind, the sense and speech also will open themselves to the Sense of our sense and to the Word behind our speech and the life to the Life of our life. The Upanishad proceeds to develop this consequence of its central suggestion by a striking parable or apologue.

The gods, the powers that affirm the Good, the Light, the Joy and Beauty, the Strength and Mastery have found themselves victorious in their eternal battle with the powers that deny. It is Brahman that has stood behind the gods and conquered for them; the Master of all who guides all has thrown His deciding will into the balance, put down His darkened children and exalted the children of Light. In this victory of the Master of all the gods are conscious of a mighty development of themselves, a splendid efflorescence of their greatness in man, their joy, their light, their glory, their power and pleasure. But their vision is as yet sealed to their own deeper truth; they know of themselves, they know not the Eternal; they know the godheads, they do not know God. Therefore they see the victory as their own, the greatness as their own. This opulent efflorescence of the gods and uplifting of their greatness and light is the advance of man to his ordinary ideal of a perfectly enlightened mentality, a strong and sane vitality, a well-ordered body and senses, a harmonious, rich, active and happy life, the Hellenic ideal which the modern world holds to be our ultimate potentiality. When such an efflorescence takes place whether in the individual or the kind, the gods in man grow luminous, strong, happy; they feel they have conquered the world and they proceed to divide it among themselves and enjoy it.

But such is not the full intention of Brahman in the universe or in the

|

13. La Parabole des dieux

APRÈS avoir affirmé qu'il est relativement possible de connaître l'inconnaissable Brahman, et justifié l'aspiration de l'âme vers cela qui est au-delà de sa condition et de sa capacité présentes, l'Oupanishad en vient aux moyens par lesquels cette haute aspiration peut se mettre en relation avec l'objet de sa recherche. Comment pénétrer à travers le voile? Et comment la conscience sujette de l'homme peut-elle entrer dans la conscience maîtresse du Seigneur? Quel pont est tendu au-dessus de ce gouffre? La connaissance a déjà été indiquée comme le moyen suprême à notre disposition, une connaissance qui commence par une sorte de réflexion de l'existence véritable dans la compréhension mentale éveillée. Mais le Mental est l'un des dieux; en vérité, la Lumière qui se tient derrière lui est le plus grand des dieux, Indra. Par l'intermédiaire de celui-ci, le plus grand d'entre eux, il s'ensuit un éveil de tous les dieux à l'essence de ce qu'ils sont, la Divinité unique qu'ils représentent. La mentalité s'ouvrant au Mental de notre mental, les sens et la parole s'ouvrent eux aussi au Sens de nos sens, au Verbe derrière notre parole, et la vie à la Vie de notre vie. L'Oupanishad va maintenant développer la conséquence de cette suggestion centrale au moyen d'une parabole, d'un apologue frappant.

Les dieux, les puissances qui affirment le Bien, la Lumière, la Joie et la Beauté, la Force et la Maîtrise, se sont trouvés victorieux dans leur éternelle bataille contre les puissances de négation. C'est le Brahman qui se tenait derrière eux et qui pour eux a vaincu; le Maître de toute chose, celui qui guide tout, a jeté dans la balance Sa volonté décisive, a rabaissé Ses enfants des Ténèbres et exalté Ses enfants de Lumière. Dans cette victoire du Maître de toute chose, les dieux ont la conscience d'un puissant développement d'eux-mêmes, d'une splendide efflorescence de leur grandeur en l'homme — de leur joie, leur lumière, leur gloire, leur puissance et leur plaisir. Mais leur vision est encore scellée à leur vérité la plus profonde; ils se connaissent eux-mêmes, mais ne connaissent point l'Éternel; ils connaissent les divinités, mais ne connaissent point Dieu. Aussi voient-ils cette victoire comme leur victoire, cette grandeur comme leur grandeur. Cette opulente efflorescence des dieux, cette exaltation de leur grandeur et de leur lumière, c'est la marche en avant de l'homme vers son idéal ordinaire: une mentalité parfaitement éclairée, une vitalité forte et saine, un corps et des sens bien ordonnés, une vie harmonieuse, riche, active, heureuse, l'idéal hellénique considéré par le monde moderne comme notre ultime potentialité. Lorsque cette efflorescence se produit, soit dans l'individu soit dans l'espèce, les |

|

creature. The greatness of the gods is His own victory and greatness, but it is only given in order that man may grow nearer to the point at which his faculties will be strong enough to go beyond themselves and realise the Transcendent. Therefore Brahman manifests Himself before the exultant gods in their well-ordered world and puts to them by His silence the heart-shaking, the world-shaking question, "If ye are all, then what am I? for see, I am and I am here." Though He manifests, He does not reveal Himself, but is seen and felt by them as a vague and tremendous presence, the Yaksha. the Daemon, the Spirit, the unknown Power, the Terrible beyond good and evil for whom good and evil are instruments towards His final self-expression. Then there is alarm and confusion in the divine assembly; they feel a demand and a menace, on the side of the evil the possibility of monstrous and appalling powers yet unknown and unmastered which may wreck the fair world they have built, upheave and shatter to pieces the brilliant harmony of the intellect, the aesthetic mind, the moral nature, the vital desires, the body and senses which they have with such labour established, on the side of the good the demand of things unknown which are beyond all these and therefore are equally a menace, since the little which is realised cannot stand against the much that is unrealised, cannot shut out the vast, the infinite that presses against the fragile walls we have erected to define and shelter our limited being and pleasure. Brahman presents itself to them as the Unknown; the gods knew not what was this Daemon.

Therefore Agni first arises at their bidding to discover its nature, limits, identity. The gods of the Upanishad differ in one all-important respect from the gods of the Rig-veda; for the latter are not only powers of the One, but conscious of their source and true identity; they know the Brahman, they dwell in the supreme Godhead, their origin, home and proper plane is the superconscient Truth. It is true they manifest themselves in man in the form of human faculties and assume the appearance of human limitations, manifest themselves in the lower cosmos and assume the mould of its cosmic operations; but this is only their lesser and lower movement and beyond it they are for ever the One, the Transcendent and Wonderful, the Master of Force and Delight and Knowledge and Being. But in the Upanishads the Brahman idea has grown and cast down the gods from this high pre-eminence so that they appear only in their lesser human and cosmic workings. Much of their other Vedic aspects they keep. Here the three gods Indra, Vayu, Agni represent the cosmic Divine on each of its three planes, Indra on the mental, Vayu on the vital, Agni on the material. In that order, therefore, beginning from the material they approach the Brahman.

Agni is the heat and flame of the conscious force in Matter which has built up the universe; it is he who has made life and mind possible and developed them in the material universe where he is the greatest deity. Especially he is the

|

dieux en l'homme deviennent lumineux, forts, heureux; ils ont le sentiment d'avoir conquis le monde et entreprennent de se le partager et d'en jouir.

Mais là ne s'arrête point l'intention du Brahman dans l'univers ou dans la créature. La grandeur des dieux est Sa propre victoire et Sa propre grandeur; elle ne leur est cependant accordée que pour permettre à l'homme de se rapprocher le plus possible du point à partir duquel ses facultés seront assez fortes pour se dépasser elles-mêmes et réaliser le Transcendant. C'est pourquoi le Brahman Se manifeste Lui-même devant les dieux exultants dans leur monde bien ordonné et, par Son silence, leur pose cette question qui fait trembler le cœur, qui fait trembler le monde: "Si vous êtes tout, alors que suis-je? Car voyez, Je suis, et Je suis ici." Bien qu'il Se manifeste, Il ne Se révèle point, mais est vu et senti par eux comme une vague et formidable présence, le Yaksha, le Daïmon, l'Esprit, le Pouvoir inconnu, le Terrible qui est au-delà du bien et du mal et pour qui bien et mal sont des instruments menant à Son expression finale. Alors c'est l'alarme et la confusion dans la divine assemblée; les dieux sentent une exigence, une menace: du côté du mal la possibilité de pouvoirs terrifiants et monstrueux, encore inconnus et non maîtrisés, qui risquent de saccager le beau monde qu'ils ont bâti, de bouleverser et mettre en pièces la brillante harmonie de l'intellect, du mental esthétique, de la nature morale, des désirs du vital, du corps et des sens qu'ils ont avec tant de peine établie; du côté du bien, l'exigence de choses inconnues qui sont au-delà de toutes les précédentes et qui, par conséquent, représentent elles aussi une menace, puisque le petit peu qui a été réalisé ne saurait tenir contre le beaucoup qui ne l'est point encore, ne saurait repousser le vaste, l'infini qui presse contre les murs fragiles que nous avons érigés pour circonscrire et protéger notre être et notre plaisir limités. Le Brahman se présente à eux comme l'Inconnu; les dieux ne savaient point ce qu'était cet Esprit.

Alors Agni, le premier, se lève à leur demande pour découvrir Sa nature, Ses limites, Son identité. Il est un point particulièrement important sur lequel les dieux de l'Oupanishad diffèrent des dieux du Rig Véda; ces derniers, en effet, ne sont pas seulement des pouvoirs de l'Un, mais sont conscients de leur source et de leur véritable identité; ils connaissent le Brahman, ils demeurent en la suprême Divinité; leur origine, leur maison, leur plan propre sont la Vérité supraconsciente. Il est vrai qu'ils se manifestent en l'homme sous la forme de facultés humaines et qu'ils assument l'apparence des limitations humaines, vrai qu'ils se manifestent dans le cosmos inférieur et assument le moule de ses opérations cosmiques; mais ce n'est là que leur mouvement secondaire, inférieur, et au-delà ils sont à jamais l'Un, le Transcendant, le Merveilleux, le Maître de la Force, du Délice, de la Connaissance, de l'Être. Par contre, dans les Oupanishads, l'idée du Brahman a grandi et a fait perdre aux dieux cette haute |

|

primary impeller of speech of which Vayu is the medium and Indra the lord. This heat of conscious force in Matter is Agni Jatavedas, the knower of all births: of all things born, of every cosmic phenomenon he knows the law, the process, the limit, the relation. If then it is some mighty Birth of the cosmos that stands before them, some new indeterminate developed in the cosmic struggle and process, who shall know him, determine his limits, strength, potentialities if not Agni Jatavedas?

Full of confidence he rushes towards the object of his search and is met by the challenge, "Who art thou? What is the force in thee?" His name is Agni Jatavedas, the Power that is at the basis of all birth and process in the material universe and embraces and knows their workings and the force in him is this that all that is thus born, he as the flame of Time and Death can devour. All things are his food which he assimilates and turns into material of new birth and formation. But this all-devourer cannot devour with all his force a fragile blade of grass so long as it has behind it the power of the Eternal. Agni is compelled to return, not having discovered. One thing only is settled that this Daemon is no Birth of the material cosmos, no transient thing that is subject to the flame and breath of Time; it is too great for Agni.

Another god rises to the call. It is Vayu Matarishwan, the great Life-Principle, he who moves, breathes, expands infinitely in the mother element. All things in the universe are the movement of this mighty Life; it is he who has brought Agni and placed him secretly in all existence; for him the worlds have been upbuilded that Life may move in them, that it may act, that it may riot and enjoy. If this Daemon be no birth of Matter, but some stupendous Life-force active whether in the depths or on the heights of being, who shall know it, who shall seize it in his universal expansion if not Vayu Matarishwan?

There is the same confident advance upon the object, the same formidable challenge, "Who art thou? What is the force in thee?" This is Vayu Matarishwan and the power in him is this that he, the Life, can take all things in his stride and growth and seize on them for his mastery and enjoyment. But even the veriest frailest trifle he cannot seize and master so long as it is protected against him by the shield of the Omnipotent. Vayu too returns, not having discovered. One thing only is settled that this is no form or force of cosmic Life which operates within the limits of the all-grasping vital impulse; it is too great for Vayu.

Indra next arises, the Puissant, the Opulent. Indra is the power of the Mind; the senses which the Life uses for enjoyment, are operations of Indra which he conducts for knowledge and all things that Agni has upbuilt and supports and destroys in the universe are Indra's field and the subject of his functioning. If then this unknown Existence is something that senses can grasp or, if it is something that the mind can envisage, Indra shall know it and make it part of his

|

prééminence, de sorte qu'ils n'apparaissent que dans leurs œuvres inférieures humaines et cosmiques. Ils conservent cependant nombre de leurs autres aspects védiques. Dans l'Oupanishad, les trois dieux, Indra, Vâyou et Agni, représentent le Divin cosmique sur chacun de Ses trois plans: Indra le mental, Vâyou le vital, Agni le matériel. C'est donc dans cet ordre, en commençant par le plan matériel, qu'ils approchent le Brahman.

Agni est la chaleur et la flamme de la force consciente qui, dans la Matière, a bâti l'univers; c'est lui qui a rendu possibles la vie et le mental, qui leur a permis de se développer dans l'univers matériel où il est la plus grande divinité. Il est tout spécialement le moteur initial de la parole, dont Vâyou est l'intermédiaire et Indra le Seigneur. Cette chaleur de force consciente dans la Matière, c'est Agni Jâtavédas, qui connaît toutes les naissances: de toutes les choses nées, de tous les phénomènes cosmiques, il connaît la loi, le processus, les limites, la relation. Lors donc, si ce qui se tient devant eux est une puissante naissance du Cosmos, quelque nouvel indéterminé qui s'est développé au cours de la lutte et du processus cosmiques, qui pourra le connaître, en déterminer les limites, la force, les potentialités, sinon Agni Jâtavédas?

Plein de confiance, il s'élance vers l'objet de sa recherche et le voilà mis au défi: "Qui es-tu? Quelle est la force qui est en toi?" Son nom est Agni Jâtavédas, le Pouvoir qui est à la base de toute naissance et de tout processus dans l'univers matériel, qui embrasse et connaît leur action, et la force en lui est telle que tout ce qui vient ainsi à naître, il peut, lui, flamme du Temps et de la Mort, le dévorer. Toutes choses sont sa nourriture, qu'il assimile et transforme en matériaux pour une nouvelle naissance, une nouvelle formation. Mais ce dévoreur qui dévore tout ne peut malgré toute sa force dévorer un fragile brin d'herbe tant que derrière celui-ci se tient la puissance de l'Éternel. Agni est contraint de s'en retourner, sans avoir rien découvert. Une seule chose est certaine: cet Esprit n'est point Naissance du cosmos matériel, point chose éphémère sujette à la flamme et au souffle du Temps; Il est trop grand pour Agni.

Un autre dieu se lève à l'appel. C'est Vâyou Mâtarishwan, le grand Principe de Vie, celui qui se meut, respire, s'épand à l'infini dans l'élément mère. Toutes choses en cet univers sont le mouvement de cette puissante Vie; c'est lui, Vâyou, qui a suscité Agni et l'a secrètement placé dans toute existence; c'est pour lui qu'ont été érigés les mondes, afin que la Vie puisse en eux se mouvoir, y agir, s'y ébattre et en jouir. Si cet Esprit n'est point né de la Matière, mais est quelque fantastique force de Vie agissant dans les profondeurs ou sur les hauteurs de l'être, qui pourra le connaître, qui pourra le saisir dans son universelle expansion, sinon Vâyou Mâtarishwan?

Et c'est le même élan assuré vers l'objet, et le même formidable défi: "Qui es-tu? Quelle est la force qui est en toi?" C'est Vâyou Mâtarishwan, et le pouvoir |

|

opulent possessions. But it is nothing that the senses can grasp or the mind envisage, for as soon as Indra approaches it, it vanishes. The mind can only envisage what is limited by Time and Space and this Brahman is that which, as the Rig-veda has said, is neither today nor tomorrow and though it moves and can be approached in the conscious being of all conscious existences, yet when the mind tries to approach it and study it in itself, it vanishes from the view of the mind. The Omnipresent cannot be seized by the senses, the Omniscient cannot be known by the mentality.

But Indra does not turn back from the quest like Agni and Vayu; he pursues his way through the highest ether of the pure mentality and there he approaches the Woman, the many-shining, Uma Haimavati; from her he learns that this Daemon is the Brahman by whom alone the gods of mind and life and body conquer and affirm themselves, and in whom alone they are great. Uma is the supreme Nature from whom the whole cosmic action takes its birth; she is the pure summit and highest power of the One who here shines out in many forms. From this supreme Nature which is also the supreme Consciousness the gods must learn their own truth; they must proceed by reflecting it in themselves instead of limiting themselves to their own lower movement. For she has the knowledge and consciousness of the One, while the lower nature of mind, life and body can only envisage the many. Although therefore Indra, Vayu and Agni are the greatest of the gods, the first coming to know the existence of the Brahman, the others approaching and feeling the touch of it, yet it is only by entering into contact with the supreme consciousness and reflecting its nature and by the elimination of the vital, mental, physical egoism so that their whole function shall be to reflect the One and Supreme that Brahman can be known by the gods in us and possessed. The conscious force that supports our embodied life must become simply and purely a reflector of that supreme Consciousness and Power of which its highest ordinary action is only a twilight figure; the Life must become a passively potent reflection and pure image of that supreme Life which is greater than all our utmost actual and potential vitality; the Mind must resign itself to be no more than a faithful mirror of the image of the superconscient Existence. By this conscious surrender of mind, life and senses to the Master of our senses, life and mind who alone really governs their action, by this turning of the cosmic existence into a passive reflection of the eternal being and a faithful reproductor of the nature of the Eternal we may hope to know and through knowledge to rise into that which is superconscient to us; we shall enter into the Silence that is master of an eternal, infinite, free and all-blissful activity.

Sri Aurobindo

|

en lui est tel qu'il peut, lui, la Vie, emporter toutes choses sans effort dans sa croissance, s'en emparer pour les dominer et pour en jouir. Mais' même cette frêle petite chose de rien du tout, il ne peut ni la saisir ni la dominer tant que le bouclier de l'Omnipotent la protège contre lui. Vâyou, lui aussi, revient sans avoir rien découvert. Une seule chose est certaine: cela n'est ni une forme ni une force de la Vie cosmique opérant dans les limites de l'impulsion vitale qui étreint toutes choses. Cela est trop grand pour Vâyou.

Alors se lève Indra, le Puissant, l'Opulent. Indra, c'est la puissance du Mental; les sens qu'utilise la Vie pour sa jouissance sont des opérations que dirige Indra pour la connaissance, et toutes choses qu'a édifiées Agni, et qu'il supporte et détruit dans l'Univers, sont le domaine d'Indra et le sujet de son fonctionnement. Alors, si cette Existence inconnue est quelque chose que les sens peuvent saisir, ou si c'est quelque chose que le mental peut envisager, Indra pourra le connaître et l'intégrer à ses opulentes possessions. Mais ce n'est rien que les sens puissent saisir ou le mental envisager, car aussitôt qu'Indra s'en approche, cela disparaît. Le mental ne peut envisager que ce qui est limité par le Temps et l'Espace, et ce Brahman est cela qui, comme l'a dit le Rig Véda, n'est ni aujourd'hui ni demain, et bien qu'il se meuve et puisse être approché dans l'être conscient de toutes les existences conscientes, quand le mental essaie de l'approcher et de l'étudier en soi, il disparaît de sa vue. L'Omniprésent ne peut être saisi par les sens, l'Omniscient ne peut être connu par la mentalité.

Cependant, contrairement à Agni et Vâyou, Indra n'abandonne pas sa recherche. Il poursuit sa route à travers le plus haut éther de la mentalité pure, et là, il rencontre la Femme, celle aux multiples splendeurs. Oumâ Haïmavatî; d'elle, il apprend que cet Esprit est le Brahman par qui seul les dieux du mental, de la vie et du corps peuvent conquérir et s'affirmer, et en qui seul ils sont grands. Oumâ est la Nature suprême d'où prend naissance toute l'action cosmique; elle est le pur sommet et le pouvoir suprême de l'Un qui resplendit ici sous de multiples formes. De cette Nature suprême, qui est aussi la Conscience suprême, les dieux doivent apprendre leur propre vérité; il leur faut pour cela refléter cette nature en eux-mêmes au lieu de se limiter à leur propre mouvement inférieur. Car elle possède la connaissance et la conscience de l'Un, alors que la nature inférieure du mental, de la vie et du corps ne peut envisager que le multiple. Aussi, bien qu'Indra, Vâyou et Agni soient les plus grands des dieux — le premier étant venu à connaître l'existence du Brahman, les autres s'en étant approchés et ayant ressenti son toucher —, c'est seulement en entrant en contact avec la conscience suprême et en reflétant sa nature, en éliminant l'égoïsme du mental, du vital et du physique afin que leur unique fonction soit de refléter l'Un et le Suprême, que les dieux en nous peuvent connaître le Brahman et le posséder. La force consciente qui supporte en nous la vie incarnée doit devenir

|

|

Compassion and gratitude are essentially psychic virtues. They appear in the consciousness only when the psychic being takes part in active life.

The vital and the physical experience them as weaknesses, for they curb the free expression of their impulses, which are based on the power of strength.

As always, the mind, when insufficiently educated, is the accomplice of the vital being and the slave of the physical nature, whose laws, so overpowering in their half-conscious mechanism, it does not fully understand. When the mind awakens to the awareness of the first psychic movements, it distorts them in its ignorance and changes compassion into pity or at best into charity, and gratitude into the wish to repay, followed, little by little, by the capacity to recognise and admire.

It is only when the psychic consciousness is all-powerful in the being that compassion for all that needs help, in whatever domain, and gratitude for all that manifests the divine presence and grace, in whatever form, are expressed in all their original and luminous purity, without mixing compassion with any trace of condescension or gratitude with any sense of inferiority.

15 June 1952 The Mother

|

purement et simplement un réflecteur de cette Conscience et de ce Pouvoir suprêmes, l'action ordinaire la plus haute de cette force n'étant jamais qu'une pâle représentation de cette Conscience et de ce Pouvoir; la Vie doit devenir une réflexion passive et puissante, une pure image de cette Vie suprême qui est plus grande que toute notre vitalité potentielle et que notre activité à son paroxysme; le Mental doit se résigner à n'être rien de plus qu'un miroir fidèle de l'image et de l'Existence supraconsciente. Grâce à cette soumission consciente du mental, de la vie et des sens au Maître de nos sens, de notre vie et de notre mental, qui seul gouverne réellement leur action, grâce à cette transformation de l'existence cosmique en une réflexion passive de l'Être éternel, en une reproduction fidèle de la nature de l'Éternel, nous pouvons espérer connaître et, par la connaissance, nous élever jusqu'à ce qui est pour nous supraconscient; nous entrerons dans le silence qui est maître d'une activité éternelle, infinie, libre, et toute-béatitude.

Sri Aurobindo

La compassion et la gratitude sont des vertus essentiellement psychiques. Elles n'apparaissent dans la conscience qu'avec la participation de l'être psychique à la vie active.

Le vital et le physique les sentent comme des faiblesses parce qu'elles mettent un frein à la libre expression de leurs impulsions basées sur le pouvoir de la force.

Comme toujours, le mental, lorsqu'il n'est pas suffisamment éduqué, est le complice de l'être vital et l'esclave de la nature physique dont il ne connaît pas bien les lois, écrasantes par leur mécanisme semi-conscient. Quand le mental s'éveille à la conscience des premiers mouvements psychiques, il les déforme dans son ignorance et change la compassion en pitié ou au mieux en charité, et la gratitude en volonté de récompenser, suivie peu à peu par la capacité de reconnaître et d'admirer.

Ce n'est que lorsque la conscience psychique est toute-puissante dans l'être, que la compassion pour tout ce qui a besoin d'être aidé, dans quelque domaine que ce soit, et la gratitude pour tout ce qui manifeste, sous quelque forme que ce soit, la présence et la grâce divines, s'expriment dans leur pureté initiale et lumineuse, sans mélanger à la compassion aucun vestige de condescendance, et à la gratitude aucun sens d'infériorité.

15 juin 1952 La Mère

|

|

There is in books a lot of talk about renunciation — that you must renounce possessions, renounce attachments, renounce desires. But I have come to the conclusion that so long as you have to renounce anything you are not on this path; for, so long as you are not thoroughly disgusted with things as they are, and have to make an effort to reject them, you are not ready for the supramental realisation. If the constructions of the Overmind — the world which it has built and the existing order which it supports — still satisfy you, you cannot hope to partake of that realisation. Only when you find such a world disgusting, unbearable and unacceptable, are you fit for the change of consciousness. That is why I do not give any importance to the idea of renunciation. To renounce means that you are to give up what you value, that you have to discard what you think is worth keeping. What, on the contrary, you must feel is that this world is ugly, stupid, brutal and full of intolerable suffering; and once you feel in this way, all the physical, all the material consciousness which does not want it to be that, will want it to change, crying, "I will have something else — something that is true, beautiful, full of delight and knowledge and consciousness!" All here is floating on a sea of dark unconsciousness. But when you want the Divine with all your will, all your resolution, all your aspiration and intensity, it will surely come. But it is not merely a matter of ameliorating the world. There are people who clamour for change of government, social reform and philanthropic work, believing that they can thereby make the world better. We want a new world, a true world, an expression of the Truth-Consciousness. And it will be, it must be — and the sooner the better!

It should not, however, be just a subjective change. The whole physical life must be transformed. The material world does not want a mere change of consciousness in us. It says in effect: "You retire into bliss, become luminous, have the divine knowledge; but that does not alter me. I still remain the hell I practically am!" The true change of consciousness is one that will change the physical conditions of the world and make it an entirely new creation.

|

De tous les renoncements, le plus difficile est de renoncer à ses bonnes habitudes.

Dans les livres, on trouve beaucoup de choses écrites sur le renoncement; il y est dit que vous devez renoncer à toute possession, à tout attachement, à tout désir. Et moi, je vous dis que tant que vous avez à renoncer à quelque chose, vous n'êtes pas encore sur ce chemin. Car, tant que vous n'êtes pas complètement dégoûté des choses telles qu'elles sont et que vous avez à faire un effort pour les rejeter, vous n'êtes pas prêt pour la réalisation supramentale. Si les constructions du Surmental, si le monde qu'il a érigé et l'ordre existant qu'il soutient, vous satisfont encore, vous ne pouvez pas espérer prendre part à la nouvelle réalisation. C'est seulement quand vous trouverez le monde actuel dégoûtant, insupportable et inacceptable que vous serez mûr pour le changement de conscience. C'est pourquoi je ne donne aucune importance à l'idée de renoncement. Si vous renoncez à quelque chose, cela veut dire que vous devez abandonner ce que vous appréciez, que vous devez rejeter ce qui vous paraît digne d'être gardé. Ce que vous devez sentir, au contraire, c'est que ce monde est laid, stupide, brutal et plein d'une souffrance intolérable; et quand vous sentez de cette manière, toute la conscience physique et matérielle qui ne veut pas qu'il en soit ainsi et travaille pour que cela change, s'écrie: "Je veux quelque chose d'autre, quelque chose qui soit vrai et beau, plein de félicité, de connaissance et de conscience. Ici tout flotte sur un océan de sombre inconscience." Mais quand vous voulez le Divin de toute votre volonté, toute votre résolution, toute votre aspiration et votre intensité, Il vient sûrement.

Cependant, il ne s'agit pas seulement d'améliorer le monde. Bien des gens réclament un changement de gouvernement, une réforme sociale, des œuvres philanthropiques, dans l'illusion qu'ils pourront ainsi rendre le monde meilleur. Mais nous, nous voulons un.monde nouveau, un monde vrai, l'expression de la Vérité-Conscience. Ce monde sera réalisé; il doit l'être; et le plus tôt sera le mieux.

Mais ce ne doit pas être seulement un changement subjectif. La vie physique tout entière doit être transformée. Ce que demande le monde matériel, ce n'est pas un simple changement de conscience en nous; il dit, en effet: "Vous vous retirez dans votre béatitude, vous devenez lumineux, vous avez la connaissance divine; mais cela ne me change pas, moi. Et je reste toujours l'enfer que je suis pratiquement!" Le vrai changement de conscience est celui qui changera les conditions physiques du monde et en fera une création entièrement nouvelle.

La Mère

|

|

Basic Issues of Indian Education*

1. In view of the present and the future of national and international living, what is it that India should aim at in education?

Prepare her children for the rejection of falsehood and the manifestation of Truth.

2. By what steps could the country proceed to realise this high aim? How can a beginning in that direction be made?

Make matter ready to manifest the Spirit.

3. What is India's true genius and what is her destiny?

To teach to the world that matter is false and impotent unless it becomes the manifestation of the Spirit.

4. How does the Mother view the progress of Science and Technology in India? What contribution can they make to the growth of the Spirit in man?

Its only use is to make the material basis stronger, completer and more effective for the manifestation of the Spirit.

5. The country feels much concerned about national unity. What is the Mother's vision of things? How will India do her duty by herself and by the world?

The unity of all the nations is the compelling future of the world. But for the unity of all nations to be possible, each nation must first realise its own unity.

6. The language problem harasses India a good deal. What would be our correct attitude in this matter?

Unity must be a living fact and not the imposition of an arbitrary rule. When

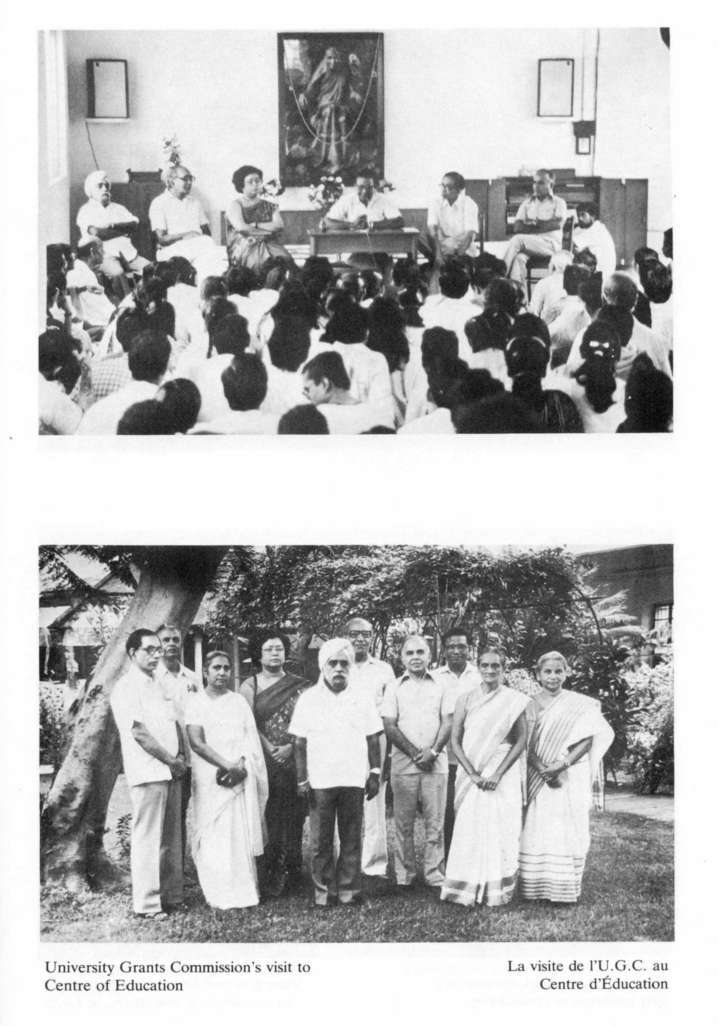

* In August 1965 an Education Commission of the Government of India visited the Ashram to evaluate the ideals and educational methods of the Centre of Education. At that time a group of teachers submitted this series of questions to the Mother. |

Principes de base de l'éducation indienne*

1. Quels doivent être les objectifs pédagogiques de l'Inde, dans la perspective présente et future de la vie nationale et internationale?

Préparer les enfants à rejeter le mensonge et à manifester la Vérité.

2. Par quelles mesures le pays peut-il s'acheminer vers la réalisation de ce but élevé? Comment amorcer un départ dans cette direction?

En préparant la matière à manifester l'Esprit.

3. Quel est le véritable génie de l'Inde et quelle est sa destinée?

Enseigner au monde que la matière est fausse et impuissante, à moins qu'elle ne devienne la manifestation de l'Esprit.

4. Comment la Mère voit-elle le progrès de la Science et de la Technologie dans l'Inde? Quelle contribution celles-ci peuvent-elles apporter à la croissance de l'Esprit dans l'homme?

Leur seule utilité est de rendre la base matérielle plus forte, plus complète et plus efficace pour la manifestation de l'Esprit.

5. L'unité nationale est une cause d'inquiétude dans tout le pays. Quelle est la vision de la Mère à cet égard? Comment l'Inde accomplira-t-elle son devoir envers elle-même et envers le monde?

L'avenir du monde tend irrésistiblement vers l'unité de toutes les nations. Mais pour que l'unité de toutes les nations soit possible, chaque nation doit d'abord réaliser sa propre unité.

6. Le problème linguistique préoccupe beaucoup l'Inde. Quelle devrait être pour nous l'attitude correcte à cet égard?

* Série de questions posées par un groupe de professeurs du Centre d'Éducation lors de la visite, en août 1965, d'une Commission d'éducation du Gouvernement indien ayant pour objet d'évaluer les idéaux et les méthodes pédagogiques du Centre.

|

|

India will be one, she will have spontaneously a language understood by all.

7. Education has normally become literacy and a social status. Is it not an unhealthy trend? But how to give education its inner worth and intrinsic en joy ability ?

Get out of conventions and insist on the growth of the soul.

8. What illusions and delusions is our education today beset with? How could we possibly keep clear of them?

a) The almost exclusive importance given to success, carreer and money.

b) Insist on the paramount importance of the contact with the Spirit and the growth and manifestation of the Truth of the being.

5 August 1965 The Mother |

L'unité doit être un fait vivant et non une règle arbitrairement imposée. Quand l'Inde sera une, elle aura spontanément une langue comprise par tous.

7. Éducation signifie normalement, de nos jours, alphabétisation et situation sociale. Cette tendance n'est-elle pas malsaine? Mais comment donner à l'éducation sa valeur intérieure et son attrait intrinsèque?

Sortez des conventions et donnez la prépondérance à la croissance de l'âme.

8. De quelles illusions et de quels leurres notre enseignement actuel est-il menacé? Comment pouvons-nous les éviter?

(a) L'importance presque exclusive accordée au succès, à la carrière et à l'argent.

(b) Donner priorité à l'importance capitale du contact avec l'Esprit, à la croissance et à la manifestation de la Vérité de l'être.

Le 5 août 1965 La Mère |

|

I MAY say, however, that I do not regard business as something evil or tainted, any more than it is so regarded in ancient spiritual India. If I did, I would not be able to receive money from X or from those of our disciples who in Bombay trade with East Africa; nor could we then encourage them to go on with their work but would have to tell them to throw it up and attend to their spiritual progress alone. How are we to reconcile X's seeking after spiritual light and his mill? Ought I not to tell him to leave his mill to itself and to the devil and go into some Ashram to meditate? Even if I myself had had the command to do business as I had the command to do politics I would have done it without the least spiritual or moral compunction. All depends on the spirit in which a thing is done, the principles on which it is built and the use to which it is turned. I have done politics and the most violent kind of revolutionary politics, ghoram karma, and I have supported war and sent men to it, even though politics is not always or often a very clean occupation nor can war be called a spiritual line of action. But Krishna calls upon Arjuna to carry on war of the most terrible kind and by his example encourage men to do every kind of human work, sarvakarmāni. Do you contend that Krishna was an unspiritual man and that his advice to Arjuna was mistaken or wrong in principle? Krishna goes further and declares that a man by doing in the right way and in the right spirit the work dictated to him by his fundamental nature, temperament and capacity and according to his and its Dharma can move towards the Divine. He validates the function and Dharma of the Vaishya as well as of the Brahmin and Kshatriya. It is in his view quite possible for a man to do business and make money and earn profits and yet be a spiritual man, practise Yoga, have an inner life. The Gita is constantly justifying works as a means of spiritual salvation and enjoining a Yoga of Works as well as of Bhakti and Knowledge. Krishna, however, superimposes a higher law also that work must be done without desire, without attachment to any fruit or reward, without any egoistic attitude or motive, as an offering or sacrifice to the Divine. This is the traditional Indian attitude towards these things, that all work can be done if it is done according to the Dharma and, if it is rightly done, it does not prevent the approach to the Divine or the access to spiritual knowledge and the spiritual life.

There is, of course, also the ascetic idea which is necessary for many and has its place in the spiritual order. I would myself say that no man can be spiritually complete if he cannot live ascetically or follow a life as bare as the barest anchorite's. Obviously, greed for wealth and money-making has to be absent from his nature as much as greed for food or any other greed and all attachment

|

TOUTEFOIS, je dois dire que je ne considère pas les affaires comme une chose mauvaise ou corrompue, et l'ancienne Inde spirituelle ne les considérait pas non plus comme telles. Si c'était le cas, je ne pourrais pas recevoir de l'argent de X ou de certains de nos disciples de Bombay qui font du commerce avec l'Afrique orientale; nous ne les encouragerions pas non plus à poursuivre leur travail, mais leur demanderions d'y renoncer et de s'occuper seulement de leur progrès spirituel. Comment concilier la quête de X pour la lumière spirituelle, et son usine? Ne devrais-je pas lui dire d'abandonner son usine à son sort et à tous les diables et d'aller méditer dans quelque ashram? Même si, moi, j'avais reçu l'intimation de me lancer dans les affaires, comme ce fut le cas pour la politique, je l'aurais fait sans le moindre scrupule spirituel ou moral. Tout dépend de l'esprit dans lequel une chose est faite, des principes sur lesquels elle est bâtie et de l'usage qu'on en fait. J'ai fait de la politique, et même de la politique révolutionnaire sous sa forme la plus violente, ghoram karma, et j'ai soutenu l'effort de guerre et envoyé des hommes se battre, bien que la politique ne soit pas toujours, soit rarement une occupation très propre, et bien qu'on ne puisse qualifier la guerre de ligne d'action spirituelle. Pourtant Krishna exhorte Ardjouna à poursuivre la plus terrible guerre qui puisse être, et, par son exemple, encourage les hommes à accomplir les œuvres humaines sous toutes leurs formes, sarvakarmâni. Soutiendrez-vous que Krishna n'était pas un homme spirituel et que ses conseils à Ardjouna étaient erronés et faux dans leur principe? Krishna va plus loin encore et déclare qu'en faisant de la façon juste et dans l'esprit juste l'œuvre que lui ont prescrit ses capacités, sa nature et son caractère fondamentaux, et cela en accord avec son propre dharma et celui de sa nature, un homme peut se diriger vers le Divin. Il valide la fonction et le dharma du vaïshya autant que ceux du brahmane et du kshatriya. Selon lui, un homme peut fort bien se lancer dans les affaires, gagner de l'argent et faire des profits, et être un homme spirituel, pratiquer le yoga, avoir une vie intérieure. La Guîtâ justifie constamment les œuvres comme moyen de salut spirituel, et prescrit un yoga des Œuvres tout autant qu'un yoga de la Bhakti ou qu'un yoga de la Connaissance. Toutefois, Krishna y superpose également une loi supérieure, selon laquelle l'œuvre doit être accomplie sans désir, sans attachement à un fruit ou une récompense quelconques, sans attitude ou mobile égoïstes, comme une offrande ou un sacrifice au Divin. Telle est l'attitude indienne traditionnelle à l'égard de ces choses; tout travail peut être fait s'il est fait en accord avec le dharma, et, s'il est accompli de la façon juste, il n'empêche pas de s'approcher du Divin ni d'accéder à la connaissance spirituelle et à la vie spirituelle.

|

|

to these things must be renounced from his consciousness. But I do not regard the ascetic way of living as indispensable to spiritual perfection or as identical with it. There is the way of spiritual self-mastery and the way of spiritual self-giving and surrender to the Divine, abandoning ego and desire even in the midst of action or of any kind of work or all kinds of work demanded from us by the Divine. If it were not so, there would not have been great spiritual men like Janaka or Vidura in India and even there would have been no Krishna or else Krishna would have been not the Lord of Brindavan and Mathura and Dwarka or a prince and warrior or the charioteer of Kurukshetra, but only one more great anchorite. The Indian scriptures and Indian tradition, in the Mahabharata and elsewhere, make room both for the spirituality of the renunciation of life and for the spiritual life of action. One cannot say that one only is the Indian tradition and that the acceptance of life and works of all kinds, sarvakarmāni, is un-Indian, European or western and unspiritual.

Sri Aurobindo |

Il y a aussi, bien entendu, l'idée ascétique qui, pour beaucoup, est nécessaire et qui a sa place dans l'ordre spirituel. Je dirais moi-même qu'aucun homme ne peut être spirituellement complet s'il ne peut vivre une vie ascétique, mener une existence aussi nue que le plus nu des anachorètes. De toute évidence, la soif d'amasser des richesses et de gagner de l'argent doit être absente de sa nature, au même titre que l'avidité pour la nourriture ou toute autre espèce d'avidité; sa conscience doit renoncer à tout attachement à ces choses. Cependant, le mode de vie ascétique n'est pas selon moi indispensable pour atteindre à la perfection spirituelle, et je n'assimile pas l'une à l'autre. Il y a la voie de la maîtrise spirituelle de soi et la voie du don de soi et de la soumission spirituels au Divin, le renoncement à l'ego et au désir au cœur même de l'action et de toutes les œuvres, quelle qu'en soit la nature, que le Divin peut nous demander d'accomplir. Autrement, il n'y aurait jamais eu en Inde ces grands hommes spirituels que furent Janaka ou Vidoura, et il n'y aurait même pas eu de Krishna; ou alors Krishna n'aurait pas été le Seigneur de Brindâvan et de Mathourâ et de Dwârakâ. ni un prince ni un guerrier ni l'aurige de Kourou-kshétra, mais seulement un grand anachorète de plus. Les Écritures indiennes et la tradition indienne, dans le Mahâbhârata et ailleurs, font place à la fois à la spiritualité du renoncement à la vie et à une vie d'action spirituelle. On ne peut dire que l'une seulement soit la tradition indienne et que l'acceptation de la vie et des œuvres de toute nature, sarvakarmâni, soit non indienne, européenne ou occidentale et non spirituelle.

Sri Aurobindo |

|

I HAVE become what before Time I was. A secret touch has quieted thought and sense: All things by the agent Mind created pass Into a void and mute magnificence.

My life is a silence grasped by timeless hands; The world is drowned in an immortal gaze. Naked my spirit from its vestures stands; I am alone with my own self for space.

My heart is a centre of infinity, My body a dot in the soul's vast expanse. All being's huge abyss wakes under me, Once screened in a gigantic Ignorance.

A momentless immensity pure and bare, I stretch to an eternal everywhere.

Sri Aurobindo |

Je suis devenu ce que j'étais avant le Temps. Un toucher secret a calmé sens et pensée: toutes les choses par l'agent du Mental créées passent dans une vide et muette magnificence.

Ma vie est un silence étreint par des mains hors-du-Temps; le monde est noyé dans un regard immortel. Nu de ses vêtements se dresse mon esprit; je suis seul avec mon propre moi pour espace.

Mon cœur est un centre de l'infinité, mon corps un point dans la vaste expansion de l'âme. De tout l'être s'éveille sous moi l'abîme énorme jadis caché dans une gigantesque Ignorance.

Immensité sans-moment pure et nue, je m'étends à un éternel partout.

Sri Aurobindo |

|

Le 2 juin 1954

Cet Entretien est basé sur le chapitre 9, "Expériences et Visions", et le chapitre 10, "Travail", de Éléments du Yoga de Sri Aurobindo.

PAS de questions?... J'allais vous offrir une méditation.

Pour quelle raison est-on incapable de méditer?

Parce qu'on n'a pas appris à le faire.

N'est-ce pas, tout d'un coup il vous prend une fantaisie: aujourd'hui je vais méditer. On ne l'a jamais fait avant. On s'assoit et on s'imagine qu'on va se mettre à méditer. Mais c'est une chose à apprendre comme on apprend les mathématiques ou le piano! On n'apprend pas ça comme ça! Il ne suffit pas de s'asseoir avec les bras croisés ou les jambes croisées pour méditer. Il faut apprendre à méditer. Partout on a donné toutes sortes de règles sur ce qu'il fallait faire pour pouvoir méditer.

Si, quand on était tout petit et que... l'on vous apprend, par exemple, à vous asseoir accroupi; si l'on vous apprenait en même temps à ne pas penser, ou à rester bien tranquille, ou à vous concentrer, ou à rassembler vos pensées ou... toutes sortes de choses qu'il faut apprendre à faire, comme méditer; si, tout petit et en même temps que l'on vous apprend à vous tenir debout, par exemple, et à marcher ou à vous asseoir, ou même à manger (on vous apprend beaucoup de choses, mais vous ne vous en apercevez pas, parce qu'on vous les apprend quand vous êtes tout petit), si on vous apprenait à méditer aussi, alors spontanément, plus tard, vous pourriez, le jour où vous le décidez, vous asseoir et méditer. Mais on ne vous l'apprend pas. On ne vous apprend absolument rien de ce genre. D'ailleurs, généralement, on vous'apprend très peu de choses — on ne vous apprend même pas à dormir. On s'imagine qu'il n'y a qu'à rester couché dans son lit et qu'ensuite on dort. Mais ce n'est pas vrai! Il faut apprendre à dormir comme il faut apprendre à manger, comme il faut apprendre à faire n'importe quoi. Et si on n'apprend pas, eh bien, on le fait mal! Ou on prend des années et des années à apprendre à le faire, et pendant toutes ces années où on le fait mal, il vous arrive toutes sortes de choses désagréables. Et c'est seulement après avoir souffert beaucoup, vous être trompé beaucoup, avoir fait beaucoup de bêtises, que, petit à petit, quand vous êtes vieux et que vous avez des cheveux blancs, vous commencez à savoir faire quelque chose. Mais si, quand on était tout petit, |

2 June 1954

This talk is based upon Sri Aurobindo's Elements of Yoga, Chapter 9, "Experiences and Visions" and Chapter 10. "Work".

No questions?... I was going to propose a meditation.

What are the causes for not being able to meditate?

Because one has not learnt to do it.

Why, suddenly you take a fancy: today I am going to meditate. You have never done so before. You sit down and imagine you are going to begin meditating. But it is something to learn as one learns mathematics or the piano. It is not learnt just like that! It is not enough to sit with crossed arms and crossed legs in order to meditate. You must learn how to meditate. Everywhere all kinds of rules have been given about what should be done in order to be able to meditate.

If, when one was quite young and was taught, for instance, how to squat, if one was taught at the same time not to think or to remain very quiet or to concentrate or gather one's thoughts, or... all sorts of things one must learn to do, like meditating; if, when quite young and at the same time that you were taught to stand straight, for instance, and walk or sit or even eat — you are taught many things but you are not aware of this, for they are taught when you are very small — if you were taught to meditate also, then spontaneously, later, you could, the day you decide to do so, sit down and meditate. But you are not taught this. You are taught absolutely nothing of the kind. Besides, usually you are taught very few things — you are not taught even to sleep. People think that they have only to lie down in their bed and then they sleep. But this is not true! One must learn how to sleep as one must learn to eat, learn to do anything at all. And if one does not learn, well, one does it badly! Or one takes years and years to learn how to do it, and during all those years when it is badly done, all sorts of unpleasant things occur. And it is only after suffering much, making many mistakes, committing many stupidities, that, gradually when one is old and has white hair, one begins to know how to do something. But if, when you were quite small, your parent or those who look after you, took the trouble to teach you how to do what you do. do it properly as it should be done, in the right way, |

|

les parents ou les gens qui s'occupent de vous prenaient la peine de vous apprendre à faire ce que vous faites, à le faire convenablement, comme il faut, d'une bonne manière, alors cela vous éviterait toutes... toutes ces fautes que vous faites pendant des années. Et non seulement vous faites des fautes, mais personne ne vous dit que ce sont des fautes! et alors vous vous étonnez quand vous tombez malade, quand vous êtes fatigué, quand vous ne savez pas faire ce que vous voulez faire et qu'on ne vous a jamais appris. Il y a des enfants à qui l'on n'apprend rien, et alors il leur faut des années, des années, des années pour apprendre la plus simple chose, même les choses les plus élémentaires: à être propres.

Il est vrai que, la plupart du temps, les parents ne l'enseignent pas parce qu'ils ne le savent pas eux-mêmes! parce qu'ils n'ont pas eu, eux aussi, quelqu'un pour leur apprendre. Alors ils ne savent pas... ils ont tâtonné toute leur vie pour apprendre à vivre. Et alors naturellement ils ne sont pas en état de vous apprendre à vivre, parce qu'ils ne le savent pas eux-mêmes! Si on vous laisse, n'est-ce pas, à vous-même, il faut des années, des années d'expériences pour apprendre la chose la plus simple, et encore il faut que vous y songiez. Si vous n'y songez pas, vous n'apprendrez jamais.

Vivre de la bonne manière est un art très difficile, et à moins qu'on ne commence à l'étudier et à faire des efforts tout petit, on ne sait jamais très bien. Simplement l'art de garder son corps en bonne santé, son esprit tranquille et une bonne volonté dans son cœur — qui sont des choses indispensables pour vivre décemment (je ne dis pas bien, je ne dis pas remarquablement, je dis seulement décemment), eh bien, je ne crois pas qu'il y ait beaucoup de gens qui prennent le souci d'apprendre cela à leurs enfants!

C'est tout?

Douce Mère, est-ce que nous devons faire quelque autre travail en dehors des études?

Quelque autre travail? Cela dépend de vous. Ça dépend de chacun et ça dépend de ce que l'on veut. Si vous voulez faire la sâdhanâ, il est évident qu'il faut avoir, au moins partiellement, une occupation qui ne soit pas égoïste, c'est-à-dire qui ne soit pas faite pour soi-même seul. L'étude, c'est très bien — c'est très nécessaire, c'est tout à fait indispensable même, justement cela fait partie des choses dont je parlais tout à l'heure, qu'il faut apprendre quand on est petit, parce que quand on est grand, cela devient beaucoup plus difficile; mais il y a un âge où on peut avoir la base d'étude indispensable et où, si l'on veut commencer à faire la sâdhanâ, il faut faire quelque chose qui n'ait pas un mobile exclusivement personnel. Il faut faire quelque chose qui soit un peu désintéressé, parce |

then that would help you to avoid all — all these mistakes you make through the years. And not only do you make mistakes, but nobody tells you they are mistakes! And so you are surprised that you fall ill, are tired, don't know how to do what you want to, and that you have never been taught. Some children are not taught anything, and so they need years and years and years to learn the simplest things, even the most elementary thing: to be clean.

It is true that most of the time parents do not teach this because they do not know it themselves! For they themselves did not have anyone to teach them. So they do not know... they have groped in the dark all their life to learn how to live. And so naturally they are not in a position to teach you how to live for they do not know it themselves. If you are left to yourself you understand, it needs years, years of experience to learn the simplest thing, and even then you must think about it. If you don't think about it, you will never learn.

To live in the right way is a very difficult art, and unless one begins to learn it when quite young and to make an effort one never knows it very well. Simply the art of keeping one's body in good health, one's mind quiet and goodwill in one's heart — things which are indispensable in order to live decently — I don't say in comfort, I don't say remarkably, I only say decently. Well, I don't think there are many who take care to teach this to their children.

Is that all?

Sweet Mother, ought we to do some other work besides studies?

Some other work? That depends upon you. It depends upon each one and on what one wants. If you want to do sadhana, it is obvious that you must have at least partially an occupation which is not selfish, that is, which is not done for oneself alone. Studies are all very well — very necessary, even quite indispensable, only it is a part of what I was speaking about just a while ago, that you must learn when you are young, for when you are grown-up it becomes much more difficult — but there-is an age when you can have the foundation of indispensable studies and when, if you want to begin to do sadhana, you must do something which does not have an exclusively personal motive. One must do something a little unselfish, for if one is exclusively occupied with oneself, one gets shut up in a sort of carapace and is not open to the universal forces. A small unselfish movement, a small action done with no egoistic aim opens a door upon something other than one's own small, very tiny person.

One is usually shut up in a shell and becomes aware of other shells only when there is a shock or friction. But the consciousness of the circulating Force, of the interdependence of beings — this is a very rare thing. It is one of the indispensable stages of sadhana.

|

|

que si vous êtes exclusivement occupé de vous-même, alors vous êtes enfermé dans une sorte de carapace et vous n'êtes pas ouvert aux forces universelles. Un petit mouvement, une petite action désintéressée qui ne soit pas faite dans un but égoïste, ouvre une porte sur quelque chose d'autre que sa petite personne, toute petite.

On est généralement enfermé dans une coquille et on ne s'aperçoit des autres coquilles que quand il y a un choc ou une friction. Mais la conscience de la Force qui circule, de l'interdépendance des êtres, cela, c'est une chose très rare. C'est l'une des étapes indispensables de la sâdhanâ.

Mère, est-ce qu'on ne peut pas étudier pour le Divin?

Ça veut dire?

On peut étudier pour le Divin et pas pour soi-même, se préparer pour l'Œuvre divine?

Oui, si vous faites l'étude avec le sentiment de vous développer pour devenir des instruments. Mais vraiment, c'est fait dans un esprit très différent, n'est-ce pas, très différent. Pour commencer, il n'y a plus de sujets qui vous plaisent ou de sujets qui ne vous plaisent pas, il n'y a plus de classes qui vous ennuient et de classes qui ne vous ennuient pas, il n'y a plus de choses difficiles et de choses qui ne soient pas difficiles, il n'y a plus de professeurs qui soient agréables et plus de professeurs qui ne le soient pas - tout cela, ça disparaît immédiatement. On se met dans un état où, quoi que ce soit qui arrive, on le prend comme une occasion d'apprendre pour se préparer à l'Œuvre divine, et tout devient intéressant. Naturellement, si on fait cela, c'est tout à fait très bien.

Ce que vous avez dit dans le Bulletin, "éduquer le mental", cela veut dire qu'on s'éduque pour cela, on vit et on étudie pour le Divin. Alors est-ce que ce n'est pas un travail pour le Divin?

Oui, oui, oui. C'est très bien si c'est dans ce but-là. Mais il faut que ce soit dans ce but-là! Par exemple, quand on veut comprendre les lois profondes de la vie, quand on veut être prêt à recevoir n'importe quel message que le Divin vous envoie, si l'on veut pouvoir pénétrer les secrets de la Manifestation, tout cela demande une mentalité développée, alors on étudie avec cette volonté-là. Mais on n'a plus besoin de faire un choix pour étudier, parce que tout et n'importe quoi, la moindre petite circonstance dans l'existence est le professeur qui peut vous apprendre quelque chose, qui peut vous apprendre à penser et à agir. |

Mother, can't one study for the Divine?

That means?

Can one study for the Divine and not for oneself, prepare oneself for the divine work?

Yes, if you study with the feeling that you must develop yourselves to become instruments. But truly, it is done in a very different spirit, isn't it? — very different. To begin with, there are no longer subjects you like and those you don't, no longer any classes which bore you and those which don't, no longer any difficult things and things not difficult, no longer any teachers who are pleasant or any who are not — all that disappears immediately. One enters a state in which, whatever happens one takes as an opportunity to learn to prepare oneself for the divine work, and everything becomes interesting. Naturally, if one is doing that, it is quite all right.

What you have said in the Bulletin, "educating the mind" — this means that one educates oneself for that, lives and studies for the Divine. Then isn't this a work done for the Divine?

Yes, yes, yes. It is very good if it is done with that aim. But it must be with that aim. For instance, when one wants to understand the deep laws of life, wants to be ready to receive whatever message is sent by the Divine, if one wants to be able to penetrate the secrets of the Manifestation, all this asks for a developed mind, so one studies with that will. But then one no longer needs to make a choice to study, for everything, no matter what, the least little circumstance in life, becomes a teacher who can teach you something, teach you how to think and act. Even — I think I said this precisely — even the reflections of an ignorant child can help you to understand something you didn't understand before. Your attitude is so different. It is always an attitude which is awaiting a discovery, an opportunity for progress, a rectification of a wrong movement, a step ahead, and so it is like a magnet that attracts from all around you opportunities to make this progress. The least things can teach you how to progress. As you have the consciousness and will to progress, everything becomes an opportunity, and you project this consciousness and will to progress upon all things.

And not only is this useful for you, but it is useful for all those around you with whom you have a contact.

Let us take simply a question about your class, shall we? — the school class. Even as an undisciplined, disobedient and ill-willed child can disorganise the |

|

Même (je l'ai dit, je crois, justement), même la réflexion d'un enfant ignorant peut vous aider à comprendre quelque chose que vous ne comprenez pas. Votre attitude est tellement différente! C'est toujours une attitude qui est dans l'attente d'une découverte, d'une occasion de progrès, d'une rectification d'un faux mouvement, d'un pas en avant, et alors c'est comme un aimant qui attire de partout l'occasion de faire ce progrès. Les moindres choses peuvent vous enseigner un progrès. Comme vous avez la conscience et la volonté de progrès, tout devient une occasion, et vous projetez cette conscience et cette volonté de progrès sur toutes choses.

Et non seulement c'est utile pour vous, mais c'est utile pour tous ceux qui vous entourent, avec qui vous avez un contact.

Prenons simplement une question de classe, n'est-ce pas, la classe à l'école. De même qu'un enfant indiscipliné, désobéissant et de mauvaise volonté peut désorganiser la classe (et c'est pour cela que, quelquefois, on est obligé de le mettre dehors, parce que simplement par sa présence il peut désorganiser complètement la classe), de même, s'il y a un élève qui a l'attitude absolument propre, la volonté d'apprendre en tout, qui fait que pas un mot n'est prononcé, pas un geste n'est fait qui ne soit pour lui l'occasion d'apprendre quelque chose, sa présence peut avoir l'effet opposé et aider la classe à s'élever dans l'éducation. Si, consciemment, il est dans cet état d'intensité d'aspiration pour apprendre et pour se corriger, il communique cela aux autres... Il est vrai que, dans l'état actuel des choses, le mauvais exemple est beaucoup plus contagieux que le bon! Il est beaucoup plus facile de suivre le mauvais exemple que le bon, mais le bon aussi est utile, et une classe avec un vrai élève qui n'est là que parce qu'il veut apprendre et qu'il veut s'appliquer, qui est profondément intéressé par toute occasion d'apprendre, cela crée une atmosphère solide.

Vous pouvez aider!

Mère, pourquoi ici, dans le travail, certaines personnes se permettent- elles de satisfaire leurs fantaisies et ainsi beaucoup d'argent est gaspillé?

Il n'y a pas que l'argent qui soit gaspillé!

L'Énergie, la Conscience est infiniment, mille fois plus gaspillée que l'argent. S'il ne devait pas y avoir de gaspillage, ma foi, je crois qu'il ne pourrait pas y avoir l'Ashram. Il n'y a pas de seconde où il n'y ait un gaspillage — il y a quelquefois pire que ça. Il y a cette habitude (qui est très peu consciente, je l'espère) d'absorber autant d'Énergie et autant de Conscience que l'on peut, et de s'en servir pour ses satisfactions personnelles. Ça, c'est une chose qui se passe à chaque minute. Si toute l'Énergie, toute la Conscience qui est constamment répandue sur vous tous était utilisée pour les fins véritables, c'est-à-dire pour

|

class — and this is why at times one is obliged to put him out, because simply by his presence he can completely disorganise the class — so too, if there is a student who has the absolutely right attitude, the will to learn in everything, so that not a word is pronounced, not a gesture made, but it becomes for him an opportunity to learn something — his presence can have the opposite effect and help the class to rise in education. If, consciously, he is in this state of intensity of aspiration to learn and correct himself, he communicates this to the others.... It is true that in the present state of things the bad example is much more contagious than the good one! It is much easier to follow the bad example than the good, but the good too is useful, and a class with a true student who is there only because he wants to learn and apply himself, who is deeply interested in every opportunity to learn — this creates a solid atmosphere.

You can help.

Mother, why is it that here, in work, some people venture to satisfy their fancies and thus much money is wasted?

It is not money alone that is wasted!

Energy, Consciousness is infinitely, a thousand times more wasted than money. Should there be no wastage... my word. I believe the Ashram couldn't be here! There is not a second when there isn't any wastage — sometimes it is worse than that. There is this habit — hardly conscious, I hope — of absorbing as much Energy, as much Consciousness as one can and using it for one's personal satisfactions. That indeed is something which is happening every minute. If all the Energy, all the Consciousness which is constantly poured out upon you all, were used for the true purpose, that is, for the divine work and the preparation for the divine work, we should be already very far on the road, much farther than we are. But everybody, more or less consciously, and in any case instinctively, absorbs as much Consciousness and Energy as he can and as soon as he feels this Energy in himself, he uses it-for his personal ends, his own satisfaction.

Who thinks that all this Force that is here, that is infinitely greater, infinitely more precious than all money-forces, this Force which is here and is given consciously, constantly, with an endless perseverence and patience, only for one sole purpose, that of realising the divine work — who thinks of not wasting it? Who realises that it is a sacred duty to make progress, to prepare oneself to understand better and live better? For people live by the divine Energy, they live by the divine Consciousness, and use them for their personal, selfish ends.

You are shocked when a few thousand rupees are wasted but not shocked when there are... when streams of Consciousness and Energy are diverted from their true purpose!

|

|

l'Œuvre divine et pour la préparation à l'Œuvre divine, nous serions déjà très loin sur le chemin, beaucoup plus loin que nous le sommes. Mais chacun, plus ou moins consciemment, et en tout cas instinctivement, absorbe autant de Conscience et autant d'Énergie qu'il le peut, et dès qu'il sent cette Énergie en lui, il s'en sert pour des fins personnelles, sa satisfaction.

Qui pense que toute cette Force qui est là, qui est infiniment plus grande, infiniment plus précieuse que toutes les forces de l'argent, cette Force qui est là et qui est donnée consciemment, constamment, avec une persévérance et une patience sans fin, seulement dans un seul but, celui de réaliser l'Œuvre divine — qui est-ce qui pense à ne pas la gaspiller? Qui est-ce qui se rend compte que c'est un devoir sacré de faire des progrès, de se préparer à mieux comprendre et à mieux vivre? Parce qu'on vit par l'Énergie divine, on vit par la Conscience divine et qu'on s'en sert pour des fins personnelles, égoïstes.

On est choqué quand il y a quelques milliers de roupies qui sont gaspillées, mais on n'est pas choqué quand il y a des... des flots de Conscience et d'Energie qui sont détournés de leurs fins véritables!

Si on veut faire une Œuvre divine sur la terre, il faut venir avec des tonnes de patience et d'endurance. Il faut savoir vivre dans l'éternité et attendre que la conscience s'éveille en chacun — la conscience de ce que c'est que la vraie honnêteté.

|

If one wants to do a divine work upon earth, one must come with tons of patience and edurance. One must know how to live in eternity and wait for the consciousness to awaken in everyone — the consciousness of what true integrity is.

The Mother

Douce Mère, Quand on vit dans une communauté, ne devient-il pas nécessaire, souvent, d'obéir aux lois imposées par les autres au lieu de suivre les disciplines que l'on voudrait pour soi-même?

Il est évident que si l'on a choisi ou accepté de vivre dans une communauté, il faut suivre les lois de cette communauté, autrement on devient un élément de désordre et de confusion.

Mais une discipline acceptée volontairement ne peut pas nuire au développement intérieur et à la croissance de la conscience supérieure.

3 octobre 1969 La Mère

Sweet Mother, When one lives in a community, does it not often become necessary to obey laws imposed by others instead of following the disciplines one would wish for oneself?

It is obvious that if you have chosen or accepted to live in a community, you must observe the laws of that community, otherwise you become an element of disorder and confusion.

But a discipline willingly accepted cannot be harmful to the inner development and the growth of the higher consciousness.

3 October 1969 The Mother |

|

But what strange ideas again! — that I was born with a supramental temperament and that I know nothing of hard realities! Good God! My whole life has been a struggle with hard realities, from hardships, starvation in England and constant dangers and hence difficulties to the far greater difficulties continually cropping up here in Pondicherry, external and internal. My life has been a battle from its early years and is still a battle the fact that I wage it now from a room upstairs and by spiritual means as well as others that are external makes no difference to its character. But, of course, as we have not been shouting about these things, it is natural. I suppose, for others to think that I am living in an august, glamorous, lotus-eating dreamland where no hard facts of life or Nature present themselves. But what an illusion all the same!

*

Fits of depression and darkness and despair are a tradition in the path of Sadhana — in all Yogas, oriental or occidental, they seem to have been the rule. I know all about them myself — but my experience has led me to the perception that they are an unnecessary tradition and could be dispensed with if one chose. That is why whenever they come in you or others I try to lift up before them the gospel of faith. If still they come, one has to get through them as soon as possible and get back into the sun. 9 April 1930

*

The worst thing for Sadhana is to get into a morbid condition, always thinking of lower forces, attacks, etc. If the Sadhana has stopped for a time, then let it stop, remain quiet, do ordinary things, rest when rest is needed — wait till the physical consciousness is ready. My own Sadhana when it was far more advanced than yours used to stop for half a year together. I did not make a fuss about it, but remained quiet till the empty or dull period was over. 8 March 1935 *

You think then that in me (I don't bring in the Mother) there was never any doubt or despair, no attacks of that kind. I have borne every attack which human |

Voilà encore des idées bien bizarres! Je suis né avec un caractère supramental et j'ignore tout des dures réalités! Seigneur tout-puissant! Toute ma vie je me suis battu avec de dures réalités, que ce soit en Angleterre, où, entre autres épreuves, j'ai connu la faim, au milieu de périls constants et des pires difficultés, ou ici même, à Pondichéry, où de bien plus grandes difficultés, tant intérieures qu'extérieures, surgissent constamment! Dès les premières années, ma vie a été un combat, et elle l'est encore: le fait qu'aujourd'hui je livre cette bataille à partir d'une chambre au premier étage, et par des moyens spirituels, et par d'autres également, qui sont extérieurs, ne change en rien sa nature. Mais comme nous ne l'avons pas crié sur les toits, il est naturel, je suppose, qu'on pense que je vis dans un pays de rêve majestueux, enchanteur, dégustant des feuilles de lotus, un lieu.protégé des dures réalités de la vie et de la Nature. Quoi qu'il en soit, quelle illusion!

*

Les accès de dépression, de désespoir, les périodes d'obscurité sont de tradition sur le chemin de la sâdhanâ — dans tous les yogas, en Orient comme en Occident, ils semblent avoir été la règle. Ils n'ont d'ailleurs aucun secret pour moi — mais l'expérience que j'en ai eue m'a fait sentir que cette tradition n'est pas obligatoire, et que l'on peut s'en dispenser, si on le veut. C'est pourquoi, chaque fois que vous, ou d'autres, souffrez de tels accès, j'essaie de brandir l'évangile de la foi. Si ces accès s'imposent malgré tout, il faut en sortir le plus vite possible et retourner au soleil. 9 avril 1930

*

Il n'y a rien de pire pour la sâdhanâ que cet état morbide où l'on pense constamment aux forces inférieures, aux attaques, etc. Si la sâdhanâ s'est interrompue pour un temps, laissez-la s'interrompre; restez tranquille, occupez-vous de choses ordinaires, reposez-vous si vous en éprouvez le besoin — attendez que la conscience physique soit prête. Ma propre sâdhanâ, alors qu'elle était beaucoup plus avancée que la vôtre, s'interrompait parfois pendant six mois. Je n'en faisais pas un drame, mais restais tranquille jusqu'à la fin de cette période vide ou morne. 8 mars 1935

* |

|

beings have borne, otherwise I would be unable to assure anybody "This too can be conquered". At least I would have no right to say so. Your psychology is terribly rigid . I repeat, the Divine when he takes on the burden of terrestrial nature takes it fully, sincerely and with out any conjuring tricks or pretence. If he has something behind him which emerges always out of the coverings it is the same thing in essence even if greater in degree, that there is behind others - and it is to awaken that that he is there.

The psychic being does the same for all who are intended for the spiritual way — men need not be extraordinary beings to follow it. That is the mistake you are making — to harp on greatness as if only the great can be spiritual. 8 March 1935

*

No joy, no energy. Don't like to read or write — as if a dead man were walking about. Do you understand the position? Any personal experience?

I quite understand; often had it myself devastatingly. That's why I always advise people who have it to cheer up and buck up.

To cheer up, buck up and the rest if you can, saying, "Rome was not built in a day" — if you can't, gloom it through till the sun rises and the little birds chirp and all is well.

Looks however as if you were going through a training in vairāgya. Don't much care for vairāgya myself, always avoided the beastly thing, but had to go through it partly, till I hit on samatā as a better trick. But samatā is difficult, vairāgya is easy, only damnably gloomy and uncomfortable. 3 June 1936

*

There is nothing peculiar about retrogression. I was also noted in my earlier time before Yoga for the rareness of anger. At a certain period of the Yoga it rose in me like a volcano and I had to take a long time eliminating it. I was speaking of a past phase. I don't know about the subconscient, must have come from universal nature. 5 August 1936 *

|